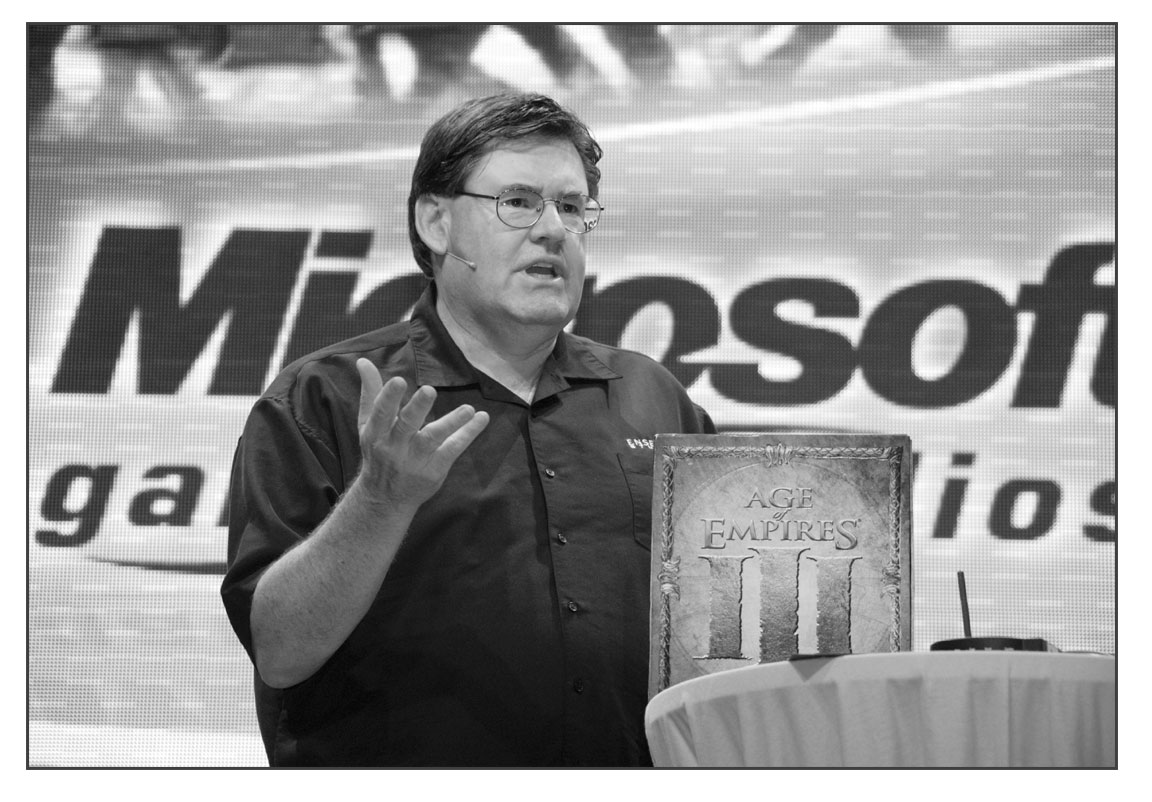

Bruce Shelley

Game Design Consultant

Bruce C. Shelley is a veteran game designer whose credits include Covert Action (1990), Railroad Tycoon (1990), Civilization (1991), Age of Empires (1997), Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings and Castleville (2011). Previously, he was a senior design director at Zynga, and a game designer at Microsoft Game Studios, Microprose Software, and Avalon Hill.

On getting into the game industry: I played games of one sort or another all of my life. I began testing board war games by mail for free and eventually landed a job with the company. I was developing board games in 1987 when my company asked me to move over to computer games, which I did. In 1988 I landed a job with Microprose and got a chance to work with Sid Meier. In 1995 an old friend asked me to join Ensemble Studios, and I was there until 2009.

On favorite games: I generally dislike this question because tastes change and games that were very important at one time are no longer even available for current operating systems or platforms. Here are five that I particularly enjoyed:

Railroad Tycoon: Working on this game was something I would have done for free if I could have made a living somehow; it was great to see Sid Meier figure out how to make a good game out of something as cool as railroading—not an easy task. The game had a fun economic model, cool trains running, multiple paths to victory, and was endlessly re-playable.

Civilization: Great fun to work on; we knew we were making something very special. It had a great hidden map, 4X game, multiple paths to victory, endlessly re-playable, levels of difficulty, a great topic, was deep and rich, and presented a very interesting stream of decisions for the player to make.

Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings: An excellent RTS in a great period, fantastic graphics, tremendous value to customers, lots of different game experiences within the same box, and a deep and rich game experience.

Empire Deluxe: A very old game but a classic that is an early and excellent example of many good design principles for strategy games: hidden maps, inverted pyramid of decision making, a great first 15 minutes, adjustable levels of difficulty, not beautiful but clean, great opportunities for strategy and tactics, simple but interesting economic system, and a great stream of interesting decisions; the one negative for me was the end game, which could drag on.

World of Warcraft/Lord of the Rings Online: Two very rich and deep online role-playing games that kept me coming back for more. Both appealed to both hard-core and casual gamers and could be enjoyed in a variety of ways. Each had an amazing variety and quantity of content to explore. WoW especially is perhaps the finest achievement in interactive games to date.

On inspiration: The single greatest resource for any game developer is all the existing games that can be played and learned from. Empire Deluxe and SimCity were great inspirations for later games that I helped design. Populous offered a lot of ideas about god games and strategy games. At Ensemble Studios we were greatly influenced by WarCraft I and II, and Command & Conquer.

On the design process: Our games have been primarily derived from existing games. We often took parts of several games and brought them together with a leavening of new ideas. The original Age of Empires, for example, was inspired by the content of Civilization and the gameplay of Warcraft and Command & Conquer. Borrowing is fine, but be careful not to imitate. Your game must be easily differentiated at a high level (AoE was about history with realistic bright graphics) and innovative at the gameplay level (AoE included randomly generated maps, multiple paths to victory, a noncheating AI, etc.). People want games similar to ones they already like, but they won’t buy the same game twice.

On prototypes: We prototyped as quickly as we could. When the game is playable we test, fix, retest, and so on in a process we call design by playing. We rely on our instincts as players to tell us when something new is working or not. Features that are fun are enhanced and polished; those that are troublesome are dropped. We plan up front based on our best ideas, but the design by playing process ensures that the game is fun when finished. I believe that extensive testing for gameplay is crucial to making fun games.

Advice to designers: Play a lot of games and analyze them. Understand why some games succeed and why others do not. Understand what is actually happening within a player’s mind when he or she is being entertained by a game. Think in terms of entertaining a large audience, not a small one. It is okay, even encouraged, to borrow from great games, but be different at the vision level (topic, look, and feel) and innovative at the gameplay level. Don’t imitate great games—people have had that experience and probably won’t pay to repeat it.